A few years ago, in the fall of 2010, a famous piece of art (The Great Wave, by Katsushika Hokusai, 1760-1849) kept re-appearing in my life. Though it contains fractal shapes, the artist, who lived more than 100 years ago, wouldn’t have called them that as the term hadn’t been invented. However, it led me back to this fascinating topic which I had briefly been introduced to about 20 years ago. I remembered my initial excitement, and the more I explored it, the more I felt this was the direction I needed to take to satisfy my artistic and my scientific nature all at once. (I have been a watercolour painter for about fifteen years, and prior to that I worked in biology). While the mathematical definition and the name (credit to Benoit Mandelbrot) are relatively new (circa 1975), the concept and patterning involved in them is hauntingly familiar. The idea of dimensions as in 1-D, 2-D and 3-D is fairly straightforward. A dot is 0-D, a curve or a line is 1-D, a surface or plane is 2-D, and a sphere or cube is 3-D, for example. But as Benoit Mandelbrot said, “Clouds are not spheres, mountains are not cones, coastlines are not circles, and bark is not smooth, nor does lightning travel in a straight line.”¹ So, what if the best way to define something’s dimensionality is to use a non-integer, like, for instance, 0.6309, or, say, 1.2618? Without going too far into the mathematics, which I myself barely understand, these are the situations where we use the term fractal. Fractals are generally self-similar, on smaller and smaller scales. There are many examples in nature, and also, many practical applications for fractal geometry in our lives.

Mandelbrot, sadly, passed away that same fall. His legacy is a novel way to observe, appreciate, and replicate the natural world. In fact, when I look at fractals, I often see everyday things. And when I look at everyday things, I often see fractals. My fractal art is an attempt to bring this idea of mine home: Fractals may not be just a model for, but may be the underlying structure of our universe.

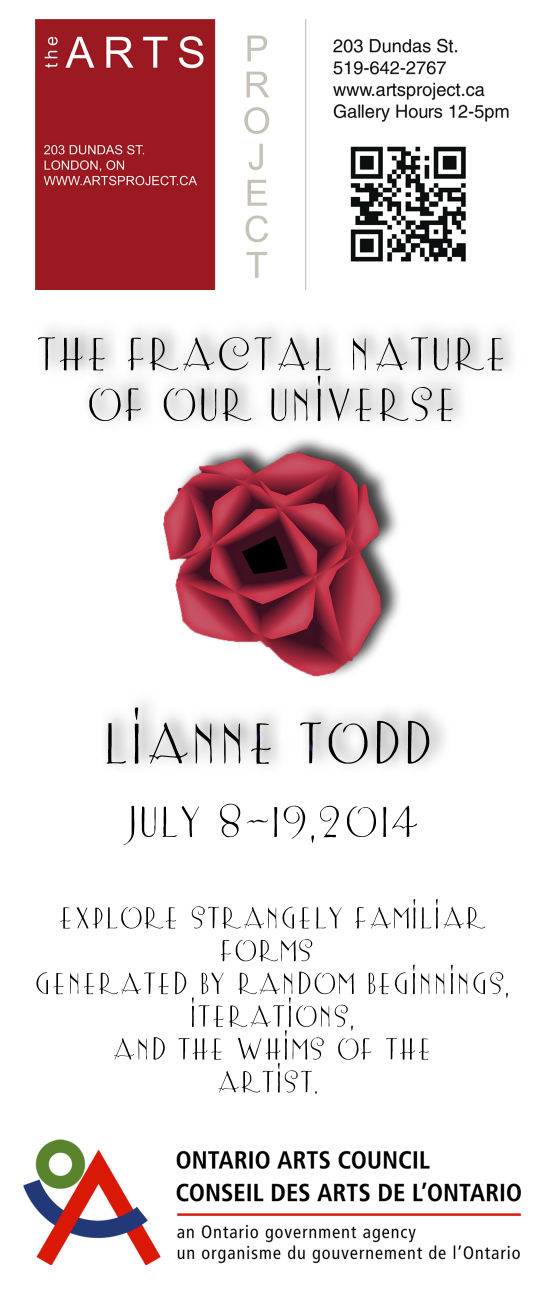

I hope you will join me in discovering a new way to look at the world. Soon, I will add photos of my creations, but for now, let me invite you to the opening reception of my solo show, The Fractal Nature of Our Universe, which introduces my fractal art to the world and is to take place on July 8, 7-9 pm in London, Ontario, Canada. Mark your calendar and follow this blog for more details at a later date!

1. MANDELBROT, B. B. 1977. The Fractal Geometry of Nature. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.